The Lost & Found Art of Film Photography

What makes film photography so special? Let's explore its enduring legacy from 1884 to the present day.

A Brief History of Film Photography

There are three eras of photography: plate, film, and digital. Today, we’ll primarily focus on the second.

Since its inception in the late nineteenth century, film photography has witnessed a fair share of ups and downs.

You may be familiar with one of its founders George Eastman. In 1884, he experimented with coating photographic emulsion—comprised of gelatinous silver nitrate—onto a flexible material.1 Four years later, he introduced the world to the first Kodak, a “simple box camera that came loaded with a 100-exposure roll of film.”2 His company’s lineup later showcased reloadable cameras carrying rolls limited to 8-12 exposures.

Eastman’s tagline was, “You push the button, we do the rest.” When he brought the more affordable Kodak Brownie camera to market at the turn of the century, this former bank clerk from Rochester, New York made photography far more accessible to the masses.

Throughout the 1900s, users didn’t have to understand the complex mechanisms behind the hardware or the chemistry of development. They only had to observe, compose, measure light, and trigger the shutter. Eventually, amateur documenters across the globe preserved their most special memories—weddings, graduations, birthdays, and travels—for generations to come.

Many other camera manufacturers elevated the visual medium to new heights. Here are some notable innovations:

1907: Cinema pioneers Louis and August Lumière marketed Autochrome, an additive color process involving plates coated with dyed starch grains.

1913: Oskar Barnack developed Ur-Leica, “the prototype of a small-format 35mm camera.”3

1928: Franke & Heidecke—later known as Rollei—popularized the Rolleiflex TLR (twin lens reflex) camera.4

1935: Eastman Kodak Company released Kodachrome, “one of the first successful color materials,” as a 16mm movie format.5 A year later, the technology expanded to 35mm slides and 8mm home movies.

1936: Ihagee created Kine Exakta, the world’s first 35mm single lens reflex (SLR) camera in regular production.6

1948: Edwin H. Land introduced the first Polaroid instant camera.

1949: Photo-Pac launched the first disposable camera.

1959: Agfa Optima became the world’s first fully automatic 35mm camera.7

1975: Eastman Kodak engineer Steven Sasson “invented the world’s first digital camera,” which weighed almost 9 pounds and resembled a toaster in size.8

1986: Fujifilm debuted the new and improved modern disposable camera.

Consumer digital cameras were first unveiled to the public during the late 1990s. For a brief window, the steep cost and learning curve slowed the technology's progression. Aside from the unique texture of grain, film—especially medium- or large-format—was also of superior quality. (In some cases, it still is!)

In the interim, most professionals and amateurs chose to stick with their tried-and-true routines. And why would the photography community turn away from film? It had helped them capture precious moments in time for more than a century.

New Developments

The transition from analog to digital officially “began in the late 1980s with the introduction of the first consumer digital cameras” and Adobe Photoshop’s debut in 1990.9 It took several more years before hobbyists and professionals adopted alternative methods of capture and storage, leaving many original pioneers in the dust.

According to Manny Almeida, former president of Fujifilm’s imaging division in North America, “The film market peaked in 2003 with 960 million rolls of film…”10 By 2004, Eastman Kodak stopped selling and manufacturing traditional film cameras across North America and Europe. The company had invented the first digital camera and invested billions in the technology’s development but failed to sustain its momentum. Nikon, Canon, Sony, and Fujifilm eventually emerged at the forefront.

With the rise of smartphones and social media applications from 2007 on, users gained the ability to snap and upload photos in a matter of seconds. There was no turning back the clock. This trend didn’t just revolutionize the photography industry. It forever changed the way humans interact.

By the time Eastman Kodak filed for bankruptcy in January 2012, many photographers had abandoned film photography to meet new demands in an “instant society” fueled by consumerism.

With the dawn of the new millennium, customers and clients have come to value—no expect—immediate gratification. This pattern doesn’t just apply to digital photography. It covers a vast swath of industries, where consumers’ buying habits influence profit margins.

Everything is fast. Fast fashion, fast food, or fast cars… But what happens when we take the time to slow down and be present?

The Analog Renaissance

2012 was not the end for Eastman Kodak or film photography. Over the past decade, there has been a resurgence.

For several years, vintage cameras—from the Nikon F3 to Canon AE-1—collected dust in basements or second-hand shops. Now, a new generation of image-makers is buying them on auction sites and beyond!

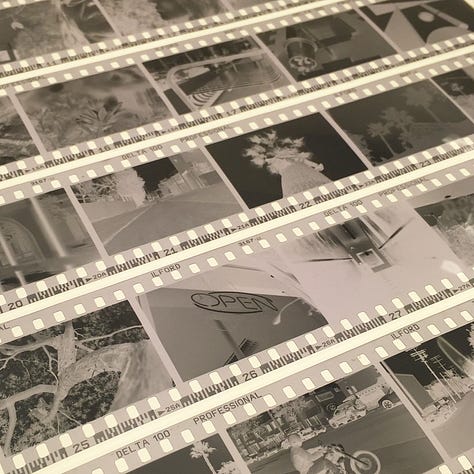

Photographers purchase prized film stocks from Ilford, Fujifilm, or Kodak—miraculously revived in 2013! However, promising leaders like CineStill offer a new angle, delivering on their promise to provide “motion picture film for still photographers.”11 Aside from producing different types and sizes of film, Lomography manufactures iconic cameras like the Diana.

Richard Photo Lab, The Darkroom, Mpix, and many other companies offer premium film development, scanning, and printing.

Even if you try it once, experiencing the film journey from start to finish is well worth the time and effort.

Fresh Perspectives

In college, I took a pre-requisite black-and-white film photography course. Some of my peers hardly gave the tests, assignments, and projects a second thought. While they quickly completed tasks for a grade, I was determined to understand the ins and outs of every process. There was a never-ending list of supplies, steps, rules, and terms… I wasn’t the fastest or most gifted, but I possessed drive.

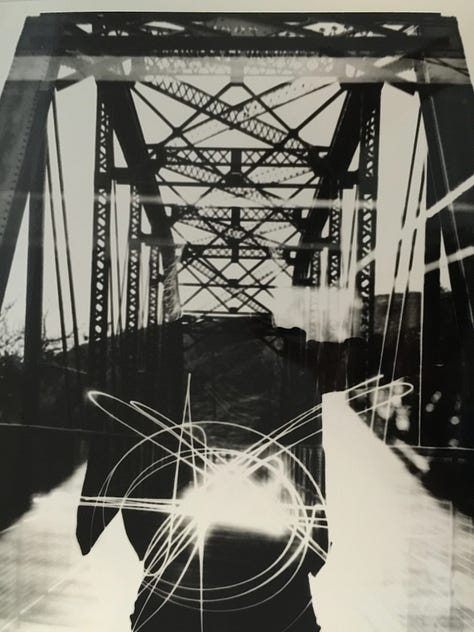

It took hours of practice in the darkroom to grow comfortable and master the fundamentals. I studied, experimented, and failed too many times to count. As I improved, every lab session became an opportunity. I embraced the unknown, experimented with new techniques, collaborated with friends, and grew leaps and bounds as a storyteller.

I’ll never forget the moment I witnessed images “magically” appear on Ilford photo paper. The feeling tied to that memory is something I’ve never stopped chasing. Who doesn’t want to transform a blank canvas and create something special out of nothing?

A few semesters later, I elected to take a color film photography class, which only intensified my passion for the lost and found art. I wanted to transport viewers. And, with the right combination of tactics and tools, I could.

Unlike digital, analog methods force photographers to slow down. There’s a delay in gratification. We observe surroundings, compose shots, adjust settings, and fire away. The final image never instantaneously appears. A roll must be finished and developed. Negatives are curated. Only then can one expose and print their photos in the dim red glow of a safelight.

One day, I hope to build my own darkroom, a silent retreat where I can pause and imagine—even if for a moment—what it was like to exist before the digital age.

Photography is a powerful communication tool. It has long existed to tell stories. Some are rooted in fact, while others are rooted in fiction. We have an extensive record of the past, but what of the future?

In 2024, people are still reinventing the wheel—or film reel in our case! There is much more to learn about this ever-evolving craft—the perfect blend of art and science. In the coming weeks, we’ll explore past and present photographic tools.