Discover 4 Types of Creativity

What kind of creative are you? Let's explore the science behind each type!

What is Creativity?

A creative is a person who designs and produces “artwork, video, copy, etc., for a business, typically in service of advertising and other aspects of marketing.”1 Some well-known examples are graphic designers, painters, writers, and filmmakers.

But creatives are not limited to artistic fields. They can occupy careers in technology, science, architecture, law, and beyond. Independent, curious, and adventurous, these pioneers challenge the status quo, inspiring others to view the world in a new light.

Creativity is a state of mind. It’s defined as “the ability to make or otherwise bring into existence something new, whether a new solution to a problem, a new method or device, or a new artistic object or form.”2

So what do influential artists, academics, makers, and visionaries have in common? They practice creatio ex nihilo. That’s Latin for “creation out of nothing.”

While some innovators begin with a blank slate (tabula rasa), others build upon previous ideas and collaborate with mentors. There is no set formula. Obstacles are guaranteed. Patience is tested. Passions ebb and flow, but still, a determined creative persists. That’s what sets them apart. They are doers.

By the end of a project, a creative usually stands in awe of their artistic contribution. They invested valuable time, energy, and talent in order to bring seemingly impossible ideas to life.

If you’re here, you must be a creative. But what kind of creativity do you practice? How do you uncover solutions, interact with collaborators, and execute ideas? Let’s unlock your potential together!

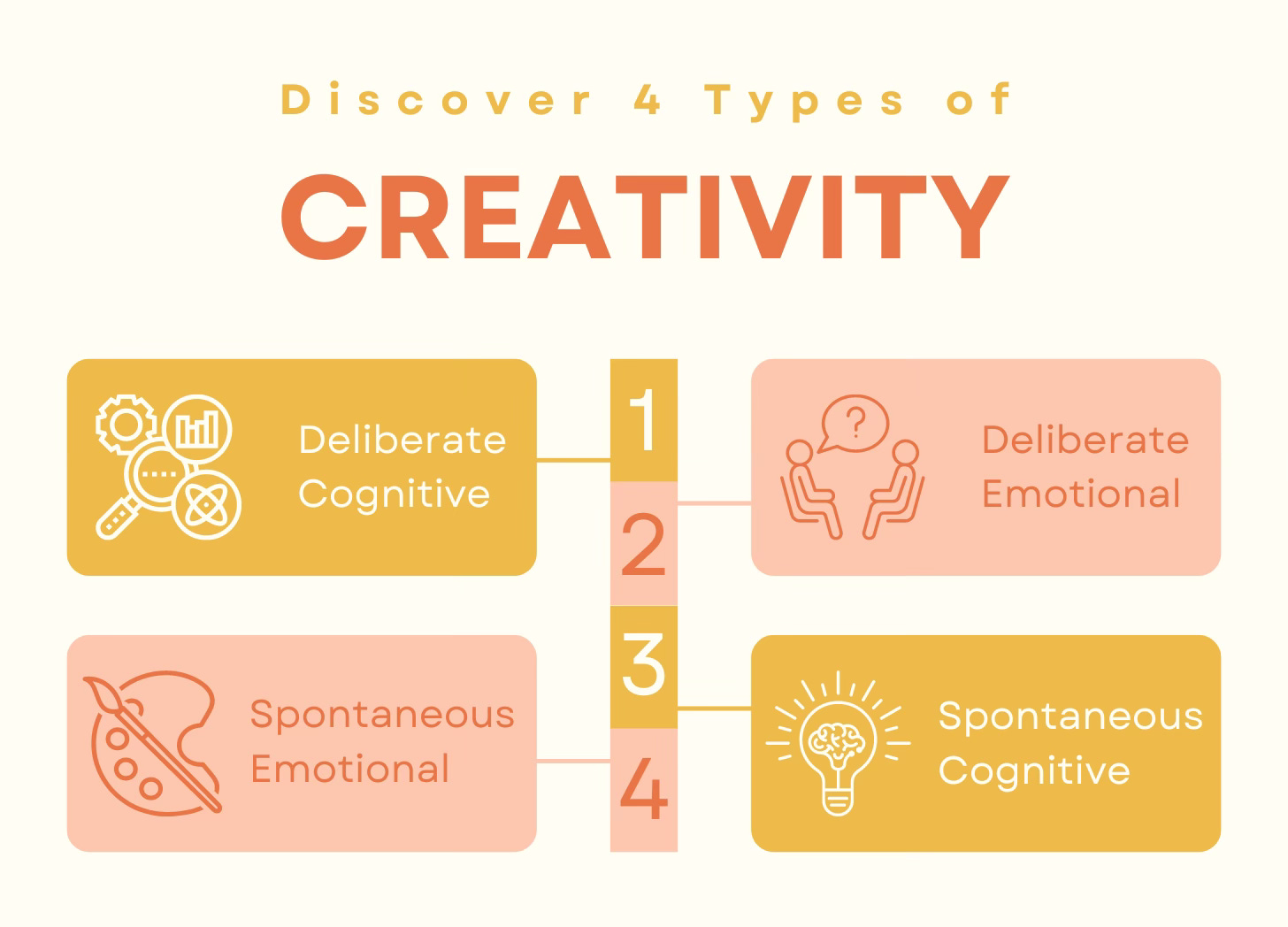

4 Types of Creativity

Cognitive neuroscience professor Arne Dietrich discovered four types of creativity based on functional neuroanatomy. His seminal paper determines that “creativity requires cognitive abilities, such as working memory, sustained attention, cognitive flexibility, and judgment of propriety…”3

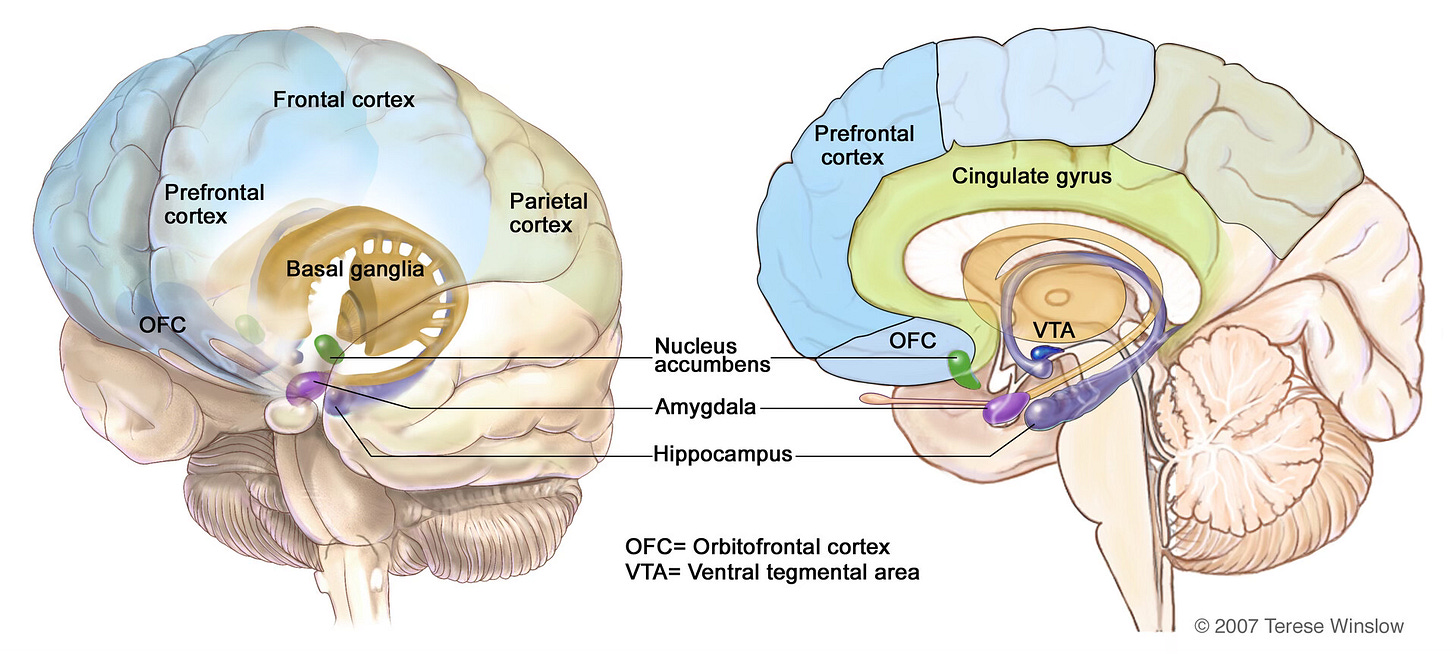

The following regions in the human brain promote creativity:

Prefrontal Cortex (PFC): One of the last parts of the brain to mature, the PFC is known as the personality center.4 It “intelligently regulates our thoughts, actions, and emotions.”5 Dietrich explains that the PFC is essential to creative expression. After evaluating “novel thoughts,” this region guides attention, retrieves relevant memories, organizes information in space-time, and weighs an idea’s potential impact. The final step is taking actions that align with internal goals.

Hippocampus: Memory, learning, emotion, and spatial awareness are the major functions of the hippocampus.6 In particular, it helps people organize and store information, effectively converting short-term memories into long-term memories.

Amygdala: The amygdala is an almond-shaped, paired structure that regulates emotion and memory. It’s associated with “the brain’s reward system, stress, and the ‘fight or flight’ response when someone perceives a threat.”7

Cingulate Gyrus: This arch-shaped structure involves a variety of processes. In addition to coordinating sensory input with emotions, the cingulate gyrus regulates emotional responses to pain, aggressive behavior, and decision-making. It also contributes to communication, maternal bonding, and language expression.8

Basal Ganglia: Aside from motor control and learning, the basal ganglia oversees executive functions and behaviors along with emotions.9

However, people are far more than their brains and bodies. We’re ever-evolving beings, shaped by personal beliefs, traditions, cultures, and emotions.

How does the brain—a complex organ with electrical activity—make sense of creativity?

1. Deliberate and cognitive creativity

Individuals with deliberate and cognitive creativity research, experiment, and investigate to achieve precise goals. An active prefrontal cortex enables them to focus and synthesize information for uninterrupted periods. Instead of viewing mistakes or errors as failures, they pivot and continue down the path of discovery with new trials. These types also expand upon past findings by accessing memories in the hippocampus.

Major Brain Centers: Prefrontal Cortex + Hippocampus

Needs: Extended time for learning and growth

Examples: Adaptive and methodical innovators like Thomas Edison or Benjamin Franklin

2. Deliberate and emotional creativity

Those who develop deliberate and emotional creativity spend time examining various angles of a problem. They ponder and ask questions until deep exploration gives way to the “a-ha moment.”

Aside from the amygdala, this type is influenced by activity in the cingulate gyrus, a portion of the brain that brings complex social emotions and memories to the forefront (e.g., prefrontal cortex). For example, during psychotherapy, people may experience profound insights. They’re suddenly able to distance themselves, distinguish feelings from facts, and gain valuable perspective.

Emotional experiences are universal, so this mode of creativity doesn’t depend on one’s professional background or accomplishments.

Major Brain Centers: Amygdala + Cingulate Gyrus + Prefrontal Cortex

Needs: Space to examine and question without excessive judgment

Examples: Therapeutic “a-ha moments” or when friends open up to each other

3. Spontaneous and cognitive creativity

Individuals experience spontaneous and cognitive creativity when seemingly random events give way to startling revelations. The proverbial light bulb turns on!

Instead of focusing time and energy on the task at hand, these creatives embrace unconscious thinking. They rely on the basal ganglia, an area of the brain that specializes in implicit learning and automatic behaviors. Activity in the prefrontal cortex, or center of command, is temporarily slowed. People remain in the moment, prioritizing their short-term “working memory.”

During the incubation stage of creativity, artists, and makers step away from their problems. This may look like walking their dog, swimming in the pool, riding a bike, washing dishes, or taking the scenic route home. These activities relieve stress, so the mind is free to wander.

It’s no surprise that many creative geniuses keep a notepad and pen on their nightstands! The best solutions arrive at unexpected moments, but your brain must be primed.

As Louis Pasteur said, “In the world of observation, chance only favors the prepared mind.”

FUN FACT: Did you know that the basal ganglia is where the feel-good neurotransmitter dopamine is stored? As a chemical messenger and hormone, it is responsible for several bodily functions: movement, memory, pleasurable reward and motivation, behavior and cognition, attention, sleep and arousal, mood, learning, and more!10

Major Brain Centers: Basal Ganglia

Needs: The right balance of activity, introspection, and rest

Examples: Archimedes and Isaac Newton’s “eureka moments” (read more here)

4. Spontaneous and emotional creativity

Moments of inspiration can strike at any time or place. Skilled painters, authors, and musicians often practice spontaneous and emotional creativity. When a powerful event occurs, creatives usually respond by making art. That’s how they understand and communicate their feelings.

Passion and instinct reign supreme. Or perhaps it’s the amygdala, the brain’s major processing center for emotions.

More than luck, it takes work to reach this milestone. Artists can spend years or even decades examining their crafts. Once they learn the rules and build a firm foundation, their most authentic selves emerge. This vulnerability is what speaks to audiences.

Major Brain Centers: Amygdala

Needs: Inspiring environments and honed skills for expression

Examples: Musicians like Mozart or painters like Picasso

Foster Creativity

Creativity is not stagnant. There will always be ups, downs, and significant shifts.

Imagine this version of yourself:

As a kid, you embraced spontaneous and emotional creativity. You didn’t worry about the future. Rooted in the present moment, you freely explored and experimented without judgment. In fact, coloring outside the lines was welcome.

In school, you were an academic with deliberate and cognitive creativity. You studied for every quiz and exam. You took the lead on class projects and didn’t stop researching until you found answers.

At work, you thrive with spontaneous and cognitive creativity. If a solution is hard to come by, you don’t fret. You trust that progress will happen in due time. After hours of hard work and brainstorming possibilities, you go to the gym, clean your house, or play fetch with your adorable dog. When you get ready for bed, an idea pops into your mind. Problem solved!

Eventually, you may receive an incredible professional opportunity. The catch? You’d have to move to a different state or country. As you consider every possibility, you may accumulate deliberate and emotional creativity. For example, you could grab coffee with your best friend. After talking and reflecting in a “therapy session,” you finally experience an “a-ha moment” leading to the best course of action.

There is no right or wrong order of types. The more life you experience, the more your creativity will flourish. As you come to understand how other people operate, observing their words and behaviors, you may be more inclined to collaborate. And the creative cycle continues!

At this stage in your life, which creative type are you? Let us know in the comments below!

Dietrich A. (2004). The cognitive neuroscience of creativity. Psychonomic bulletin & review, 11(6), 1011–1026. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03196731

Hathaway, W. R., & Newton, B. W. (2023). Neuroanatomy, Prefrontal Cortex. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

Arnsten A. F. (2009). Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 10(6), 410–422. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2648

Anand, K. S., & Dhikav, V. (2012). Hippocampus in health and disease: An overview. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, 15(4), 239–246. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-2327.104323

Lanciego, J. L., Luquin, N., & Obeso, J. A. (2012). Functional neuroanatomy of the basal ganglia. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine, 2(12), a009621. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a009621